The Two Lost Sons

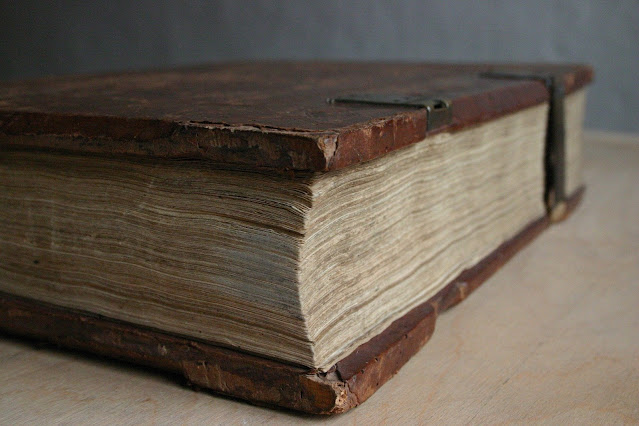

I just finished a book by Tim Keller about the parable from Luke 15 traditionally found under the subhead The Prodigal Son. The book has provided so much more insight into the parable than I've ever known and has challenged me more than anything I've read in a long time. Since so much of what I'm going to say is from the book, I'll go ahead and post a link to it: The Prodigal God.

*All page number references are to this edition.

The Parable of the Two Lost Sons

Keller first makes the point that a more accurate title of this parable would be the Parable of the Two Lost Sons as the traditional focus on the younger brother may do injustice to the text (keep in mind that the chapter and verse divisions, as well as the subheads in the Bible are not part of the original writings, so this suggestion does no harm to Keller's high view of the Bible's textual integrity and reliability). He bases this idea primarily on the makeup of Jesus's direct audience when the story is told. Though the majority of the text focuses on the younger brother's story, the heart of the text may be the elder brother. When Jesus told this story, there were two groups listening: the tax collectors and sinners (analogous with the younger brother), and the Pharisees and teachers of the law (analogous with the elder brother). Jesus tells this parable in response to the self-righteous mutterings of the Pharisees and teachers of the law about how Jesus associates with the tax collectors and sinners.

Jesus's description of the brothers presents two primary ways in which people are alienated from God and seek acceptance into God's Kingdom (and shows how both actually represent spiritual lostness). Theare shown in how happiness and fulfillment are sought: either through self-discovery or moral conformity. The way of self-discovery "holds that individuals must be free to pursue their own goals and self-actualization regardless of custom and convention. In this view, the world would be a far better place if tradition, prejudice, hierarchical authority, and others barriers to personal freedom were weakened or removed" (35-36). This is the way of the younger brother, who squandered his inheritance on wild and sensual living until he had nothing left. The way of moral conformity, by contrast, "[puts] the will of God and the standards of the community ahead of individual fulfillment" (35) so that happiness is obtained and the world is made right by achieving moral rectitude. This is the way of the elder brother, who faithfully served his father and honored customs.

Which approach is right?

Neither! It's not just the son that went away and returned that was alienated from his father; so was the elder brother who never left! Both wanted the same thing: the father's goods, rather than the father himself. Both used their father for the same self-serving ends, albeit in very different ways. Rebellion against God can be found in "breaking [God's] rules or keeping all of them diligently" (42). Both sons tried to displace the father's authority, which can show the ultimate definition of sin: "putting yourself in the place of God as Savior, Lord, and Judge" (50). The younger son demanded his freedom and sought to define what was right and wrong for his own life. The elder son used obedience as a way of getting what he ultimately wanted. Both have a radically self-centered heart and avoid Jesus as Savior, which is the essence of sin and lostness.

In confronting the Pharisees and teachers of the law with the parable, Keller suggests that Jesus implies that the condition of the elder brother may be more dangerous. The young brother repents of his sins and returns to the father, where he is freely welcomed and celebrated. We don't see a similar outcome for the elder brother. He stays in his self-righteous, moral lostness-unaware of his need to repent of his good deeds from a self-centered heart. Elder brothers expect their good lives to pay off and may be in a more dangerous position because of their blindness to their own lostness. The elder brother was kept out of the feast of salvation based on pride over his good deeds, not remorse over any bad deeds (86). "The main barrier between the Pharisees (elder brothers) and God is not their sins, but their damnable good works" (87). True repentance must be done not only for the things we have done wrong, but also for the reason behind why we ever do anything right (when it's to be our own lord and savior by seeking to control God) (87).

Which Brother Am I?

What I did not realize about myself before reading this book is just how much I am the elder brother in this parable. I am in just as much need for repentance and salvation from my self-righteous and pride-driven good works as the younger brothers who live outwardly licentious lives. The proneness to use Jesus as a means to the best-available outcome when it's all said and done, rather than an ends in himself, is ever present in me. It's not always there, but it's easy to fall into the trap. What's not easy is realizing this about oneself. The following are given as clues that this 'elder brother' heart is present in your good deeds/moral living/religious practice:

- When things go wrong you either: get angry with God if you know you've been living as you should; OR you are filled with self-loathing if you know you've been falling short of your standards. This means that your moral observances are results-oriented (57-58). True faithfulness is to be born out of love for and delight in God. Check.

- You have a strong sense of your own superiority. You are defined by competitive comparison, have difficulty truly forgiving others (but not necessarily confessing forgiveness), and feel you have been given a right to feel highly offended by others (60-65). We should be slow to anger, quick to forgive, and always aware that the self-centered hearts we see in others is also in us. Check.

- You have "joyless, fear-based compliance" (65). There is not joy or love in just seeing the Father pleased. We want to see ourselves as virtuous and earn blessings from the Father. This creates the pressure to appear, even often to ourselves, as happy and content even if we aren't experiencing such. This is a sign that our righteousness is drudgery, not joy-driven. Check.

- You have a lack of assurance of the Father's love. We think when something goes wrong, it's because we're not living as we should. Criticism devastates us. And we feel irresolvable guilt when we do wrong, even after repenting (71-72). Check.

- You have a dry prayer life. There may be frequent prayer, but it lacks intimacy, delight, or awe. Prayer is probably more frequent when things are going wrong, until they get back on track. This indicates that the main goal of prayer for you is "to control [your] environment rather than to delve into an intimate relationship with a god who loves [you]" (74).

The first thing is to realize the the gospel calls us away from both ways of living. We need to repent of not only all of our sinful deeds and behaviors, but also of our selfish reasons for our good deeds before God. We are to put our ultimate hope in God himself, not in what He will give us as a result of our goodness. For this we need to accept God's initiating love, understanding that "it's not the repentance that causes the Father's love, but rather the reverse" (83).

The second is to realize that our rebellion against God-whether as younger brothers or elder brother-results in alienation that demands a price. For us to be restored this price can only be paid by someone who has not been alienated from God. That person is the true elder brother, Jesus. He was stripped of his dignity on the cross so that we could be clothed with a standing we don't deserve. He was treated as an outcast so we could be brought in. He drank the cup of the Father's justice so we could drink the cup of the Father's joy (95-96). There is no other way we can be brought in. When we see this, the way that our hearts function is transformed. We are attracted to his beauty, love, and greatness. The fear and neediness that creates young and elder brothers is eliminated (99).

When we see this, our desires and duties are fused. We don't have to turn from God to pursue the desires of our hearts like the younger brother, and we don't have to repress our desires and perform our moral duty like the elder brother (99). They become one and the same. John Newton states it in this way.

Our pleasure and our duty

though opposite before,

since we have seen his beauty

are joined to part no more.

In Christ, we are brought back home to the true home that we were created for and for which all of our desires ultimately point: the presence of God himself, where there is joy to the full and pleasures forevermore. We are invited to this great, eternal feast. Whether we are elder brothers or younger brothers, Christ's work is sufficient and his grace is enough. We are never too lost in our sin or too deluded in our righteousness to be beyond the grasp of Jesus's atoning work on the cross. Once our hearts see this, we are captivated.

Comments

Post a Comment